Adaptive Optics Kits

- Kits Include All Necessary Optics, Hardware, and Standalone Control Software

- Up to 190 Hz Closed-Loop Operation with CMOS Wavefront Sensor

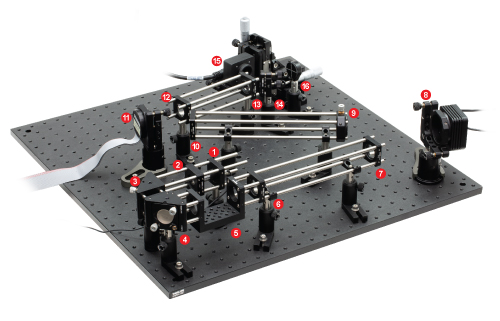

Assembled AOK5

MEMS Deformable Mirror Kit

(Breadboard Not Included)

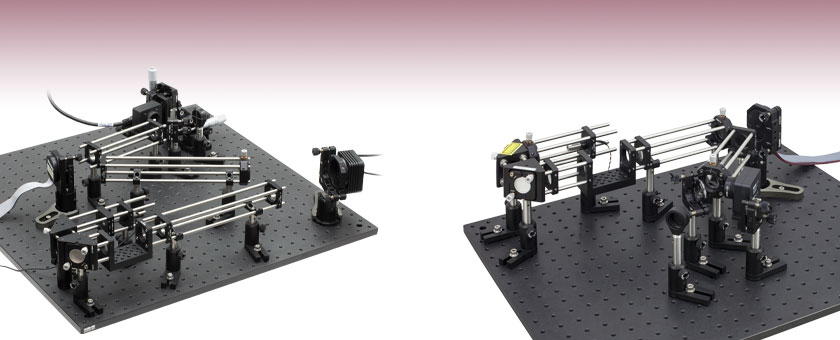

Assembled AOKWT1

Woofer-Tweeter Kit

(Breadboard Not Included)

OVERVIEW

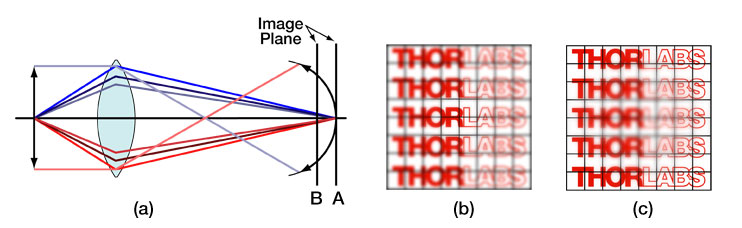

Resolution target imaged using (a) a flat mirror (b) an optimized deformable mirror.

The smallest lines are separated by 2 μm.

Features

- Complete Kit and Software for Out-of-the-Box Wavefront Measurement and Control

- Options with One Deformable Mirror (DM) or a Woofer-Tweeter Configuration with Two DMs

- Each Kit Includes (See the Components Tab for Details):

- One or Two Continuous Surface DM(s)

- Shack-Hartmann Wavefront Sensor (880 fps Max CMOS Sensor)

- Laser Diode Module (635 nm)

- All Imaging Optics and Associated Mounting Hardware

- Fully Functional Standalone Control Software for Windows

- SDK for Custom Applications Authored by the End User

- Two Protected Silver-Coated Deformable Mirror Options Available Below:

- 140-Actuator MEMS Deformable Mirror

- 40-Actuator Piezoelectric Deformable Mirror

- Custom Kits with Other Mirror Coatings, Mirror Types, and Wavefront Sensors Available by Contacting Tech Support (See the Custom AO Kits Section Below for Options)

Each Thorlabs Adaptive Optics (AO) Kit is a complete adaptive optics imaging solution, including one or two deformable mirrors (DMs), a wavefront sensor (WFS), control software, and optomechanics for assembly. These precision wavefront control devices are useful for beam shaping, microscopy, laser communications, and retinal imaging as well as educational demonstrations. To learn more about how the wavefront sensor, deformable mirror, and software operate as a closed-loop system to correct wavefront distortion, please see the various tabs on this page or the Adaptive Optics 101 white paper.

In addition to AO kits based on a single MEMS-based or piezoelectric DM, Thorlabs also offers the AOKWT1(/M) woofer-tweeter AO kit that includes one of each type of DM. In a woofer-tweeter AO system, two deformable mirrors are used in conjugate planes, such that one mirror (a woofer) corrects for lower order aberrations and the other, the tweeter, corrects higher order aberrations.

Please note that a breadboard is not included. We recommend building the single-DM AO kits on an 18" x 24" (450 mm x 600 mm) breadboard such as Item # MB1824 (MB4560/M) and the dual-DM AO kit on a 24" x 24" (600 mm x 600 mm) breadboard such as Item # MB2424 (MB6060/M). The kit does not include the 1/4"-20 (M6) screws needed to mount the kit to an optical table or breadboard.

Deformable Mirror(s)

The kits below are available with a protected silver-coated MEMS deformable mirror with 140 actuators or piezoelectric deformable mirror with 40 actuators. The woofer-tweeter kits come with one of each type of mirror. Custom kits including other MEMS or piezoelectric DMs can be ordered by contacting Tech Support; options are outlined in the Custom AO Kits section below.

Wavefront Sensor

Each adaptive optics kit offered below includes a high-speed 880 fps (max) CMOS-based Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor. Custom kits are also available by contacting Tech Support.

Custom AO Kits

In addition to the stock options offered below, we can create custom AO kits using different combinations of the deformable mirrors (DMs) and wavefront sensors (WFS) offered in our catalog. Please contact Tech Support with inquiries.

Wavefront Sensor Options

Deformable Mirror Options

SPECS

| AO Kit Item # | Included Deformable Mirror(s) | Included Wavefront Sensor |

|---|---|---|

| AOK5(/M) | DM140A-35-P01 MEMS-Based DM | WFS20-5C(/M) |

| AOK8(/M) | DMH40(/M)-P01 Piezoelectric DM | |

| AOKWT1(/M) | DM140A-35-P01 MEMS-Based DM and DMH40(/M)-P01 Piezoelectric DM |

| Deformable Mirror Item # | DM140A-35-P01 | DMH40-P01 (DMH40/M-P01) |

|---|---|---|

| Deformable Mirror Type | Boston Micromachines MEMS Multi-DM | Piezoelectric DM |

| Included In | AOK5(/M) AOKWT1(/M) |

AOK8(/M) AOKWT1(/M) |

| Actuator Array | 140 Actuators in a 12 x 12 Arraya | 40 Piezoceramic Disk Segments in a Circular Keystone Array (Elements 1 - 24 Inside Pupil Diameter, Elements 25 - 40 Outside Pupil Diameter) |

| Segment Voltage Range | N/A | 0 to 300 V (Default: +150 V on Actuator Array for Flat Mirror) |

| Stroke (Max) | 3.5 µm per Actuator | Defocusb: ±17.6 µm Astigmatismb: ±18.4 µm Comab: ±6.8 µm Trefoilb: ±6.5 µm Tetrafoilb: ±5.7 µm Secondary Astigmatismb: ±3.0 µm Third Order Spherical Aberrationb: ±2.7 µm |

| Actuator Pitch | 400 µm | N/A |

| Clear Aperture | 4.4 mm x 4.4 mm | Ø17.0 mm |

| Pupil Dimensions | N/A | Ø14.0 mmc |

| Mirror Coating (Click for Plot) | Protected Silver | Protected Silver |

| Mirror Wavelength Range | - | 450 nm - 2 µm: Ravg > 97.5%, 2 - 20 µm: Ravg > 96% |

| AR Coated Window Wavelength Range (Click for Plot) | 400 - 1100 nmd | - |

| Surface Quality | <30 nm RMS | - |

| Surface Flatness | - | 200 nm RMS (Defocus Term Actively Flattened) |

| Average Step Size | <1 nm | N/A |

| Hysteresis | None | 20% Typical, 25% Max |

| Fill Factor | >99%e | 100% |

| Response Time | <75 μs (~13.3 kHz) Mechanical Response Time (10% - 90%) | 0.5 ms (Full Stroke) Mirror Response Time |

| Interactuator Coupling, CDMf | 13% | See Footnote b |

| Frame Rate (Max) | 2 kHz | 4.0 kHz via USB 2.0 (Over Entire Voltage Range) |

| Resolution | 14 Bit | N/A |

| Head Dimensions | Ø2" x 0.89" (Ø50.8 mm x 22.5 mm) |

64.0 mm x 60.0 mm x 30.9 mm (2.52" x 2.36" x 1.22") |

| Driver Dimensions | 9.0" x 7.0" x 2.5" (229 mm x 178 mm x 64 mm) |

N/A |

| Computer Interface | USB 2.0 | |

| Wavefront Sensor Item # | WFS20-5C(/M)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Wavefront Sensor Type | CMOS-Based Sensor | |

| Included In | AOK5(/M) AOK8(/M) AOKWT1(/M) |

|

| Frame Rate (Max) | 880 fps | |

| Camera | ||

| Aperture Size (Max) | 7.20 mm x 5.40 mm | |

| Resolution (Max) | 1440 x 1080 Pixels, Selectable | |

| Pixel Size | 5.0 x 5.0 µm | |

| Shutter | Global | |

| Exposure Range | 4 µs - 83.3 ms | |

| Image Digitization | 8 Bit | |

| Microlens Array | ||

| Wavelength Range | 300 - 1100 nm | |

| Lenslet Pitch | 150 µm | |

| Lenslet Diameter | Ø140 µm | |

| Number of Lenslets (Max) | 47 x 35 | |

| Effective Focal Length | 4.1 mm | |

| Substrate | Fused Silica (Quartz) | |

| Coating | Chrome Mask | |

| Wavefront Measurement | ||

| Accuracy @ 633 nm (RMS) | λ/30 | |

| Sensitivity @ 633 nm (RMS) | λ/100 | |

| Dynamic Range @ 633 nm | >100λ | |

| Local Radius of Curvature | >7.4 mm | |

| Housing Dimensions and Threads | ||

| Optical Input Connector | C-Mount (1.00"-32) | |

| Physical Size (H x W x D) | 46.0 mm x 56.0 mm x 33.1 mm (1.81" x 2.20" x 1.30") |

|

| Warm-Up Time for Rated Accuracy | 15 minutes | |

| Power Supply | External; 12 V DC, 1.5 A | |

| Operating Temperature | 5 to 35 °C | |

| Storage Temperature | -40 to 70 °C | |

DM

Click to Enlarge

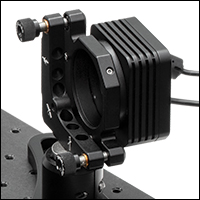

The Piezoelectric DM mounted on its circuit board. The three piezoelectric ceramic arms used for tip and tilt correction are seen around the edges of the mirror.

A close-up of the MEMS DM electrical interface to show the wiring of the chip.

| Included Deformable Mirrors in AO Kitsa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kit Item # | Mirror Type | Actuator Array | Mirror | Coating |

| AOK5(/M) | MEMS | 12 x 12 | DM140A-35-P01 | Protected Silver |

| AOK8(/M) | Piezoelectric | 40 | DMH40-P01 (DMH40/M-P01) |

|

| AOKWT1(/M) | MEMS | 12 x 12 | DM140A-35-P01 | |

| Piezoelectric | 40 | DMH40-P01 (DMH40/M-P01) |

||

Selecting a Deformable Mirror

Ideally, the deformable mirror (DM) needs to assume a surface shape that is complementary to, but half the amplitude of, the aberration profile in order to compensate for the aberrations and yield a flat wavefront. However, the actual range of wavefronts that can be corrected by a particular deformable mirror is limited by several factors:

- Actuator stroke is another term for the dynamic range (i.e., the maximum displacement) of the deformable mirror actuators and is typically measured in microns. Inadequate actuator stroke leads to poor performance by limiting aberration amplitudes that may be compensated, preventing the convergence of the control loop.

- The number of actuators limits the degrees of freedom of the wavefront control system, and therefore the complexity of the wavefront that may be corrected.

- The speed of the deformable mirror is important if you are trying to correct for rapidly changing wavefronts. For mirrors that exhibit hysteresis (i.e., piezoelectric deformable mirrors), the control software will need to calculate the correct voltage changes to produce the desired mirror displacement, which can lower the mirror speed.

- Optical power handling will also vary depending on the mirror coating and actuator design. For our mirrors, the piezoelectric deformable mirrors have significantly higher power handling than the MEMS systems [up to 1 J/cm² (1064 nm, 10 ns, 10 Hz, Ø10 mm)]. They can also be custom coated to operate inside laser cavities (contact techsupport@thorlabs.com for details).

- Hysteresis in piezoelectric deformable mirrors means that the displacement of a mirror segment at a given voltage is different if that voltage is approached from a higher voltage compared to a lower voltage. Our AOK8(/M) adaptive optics (AO) kit uses a piezoelectric deformable mirror and offers hysteresis compensation, while the MEMS-based deformable mirror used in our AOK5(/M) AO kit are inherently hysteresis-free; the AOKWT1(/M) kit comes with one of each mirror. The hysteresis compensation for the piezoelectric deformable mirrors can be turned off when operating the mirror with open-loop control, which can increase the speed.

The first four considerations are physical limitations of the deformable mirror itself, whereas hysteresis may be a limitation of the control software and/or a physical limitation of the mirror itself. Additionally, the wavelength range of the deformable mirror coating and any protective windows installed in the mirror head must be appropriate for the application wavelength.

Comparison

Thorlabs' piezoelectric deformable mirrors provide a larger stroke, and therefore are able to correct for larger wavefront deviations, than our MEMS deformable mirrors. However, they contain a lower density of actuators over the active area of the mirror than the MEMS deformable mirrors, which means they cannot correct wavefront deviations on as fine of a spatial scale as the MEMs deformable mirrors. While the piezoelectric deformable mirrors do experience hysteresis, the control software includes integrated hysteresis compensation to minimize the impact of this effect.

| MEMS Deformable Mirrors Selection Guidea | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mirror Item # | Actuator Array | Coating |

| DM140A-35-UP01 | 12 x 12b | Aluminum |

| DM140A-35-P01 | Protected Silverc | |

| DM140A-35-UM01 | Gold | |

Click to Enlarge

12 x 12 Actuator Multi DM

12 x 12 MEMS Deformable Mirrors

- 12 x 12 Actuator Array (140 Active)

- 3.5 μm Maximum Actuator Displacement

- High-Speed Operation up to 3.5 kHz

- 400 μm Center-to-Center Actuator Spacing

- Low Inter-Actuator Coupling Results in High Spatial Resolution

- Zero Hysteresis Actuator Displacement

- 14-Bit Drive Electronics Yield Sub-Nanometer Repeatability

- Compact Driver Electronics with Built-In High-Voltage Power Supply Suitable for Benchtop or OEM Integration

Through our partnership with Boston Micromachines Corporation (BMC), Thorlabs is pleased to offer BMC's Multi- Micro-electro-mechanical (MEMS)-based Deformable Mirrors as part of our adaptive optics kits. These DMs are ideal for advanced optical wavefront control; they can correct monochromatic aberrations (spherical, coma, astigmatism, field curvature, or distortion) in a highly distorted incident wavefront. MEMS deformable mirrors are currently the most widely used technology in wavefront shaping applications given their versatility, maturity of technology, and the high resolution wavefront correction capabilities they provide.

Click to Enlarge

MEMS Deformable Mirror Structure

These deformable mirrors, fabricated using polysilicon surface micromachining fabrication methods, offer sophisticated aberration compensation in easy-to-use packages. The mirror consists of a mirror membrane that is deformed by 140 electrostatic actuators (i.e., a 12 x 12 actuator array with four inactive corner actuators). These actuators provide 3.5 μm of stroke (over 11 waves at 632.8 nm) with zero hysteresis.

The AOK5(/M) and AOKWT1(/M) AO Kits each include a MEMS DM with a protected silver (-P01) coating. Custom kits with are available with aluminum (-UP01) or gold (-UM01) coated mirrors (see the MEMS Deformable Mirrors Selection Guide above). Each mirror is protected by a 6° wedged window that has a broadband AR coating for the 400 - 1100 nm range. See the coating curve graphs below for details. Custom coatings are available for the protective window; please contact Tech Support for more information.

BMC's Multi-DMs are also available separately. Click here for more information.

Click to Enlarge

Reflectance of the AR-Coated, 6° Wedged Window on the DM140A-35 Mirrors

Click to Enlarge

Reflectance of the DM140A-35 Metallic Mirror Coatings

| Piezoelectric Deformable Mirrors Selection Guidea | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mirror Item # | Actuator Array (Click for Diagram) | Coating |

| DMP40-F01 (DMP40/M-F01) | 40 in a Circular Keystone Array and 3 Tip/Tilt Spiral Arms |

UV-Enhanced Aluminum |

| DMP40-P01 (DMP40/M-P01) | Protected Silver | |

| DMH40-F01 (DMH40/M-F01) | 40 in a Circular Keystone Array | UV-Enhanced Aluminum |

| DMH40-P01 (DMH40/M-P01) | Protected Silverb | |

40 Actuator Piezoelectric Deformable Mirrors

Click to Enlarge

40 Actuator DMH40(/M)-P01 Deformable Mirror

- Mirror is Deformed by 40 Electrodes Attached to a Single Piezoceramic Disk

(See Diagrams in the Table to the Right) - UV-Enhanced-Aluminum- or Protected-Silver-Coated Mirror

- Deformable Mirrors with Tip-Tilt Actuation (DMP40 Series) Have Ø10.0 mm Active Area

- High-Stroke Deformable Mirrors (DMH40 Series) Have Ø14.0 mm Active Area

- Integrated Hysteresis Compensation

- 4 kHz Max Update Rate

- Mirror Head Includes Built-In High-Voltage Driver

- Software Program for Mirror Control Incorporates Hysteresis Compensation

For applications requiring larger stroke than the MEMS-based mirrors can provide, Thorlabs is pleased to offer piezoelectric deformable mirrors as part of our AO kits. These deformable mirrors are ideal for correcting distortions that result from common sources of wavefront aberrations, such as astigmatism and coma (see the Aberrations tab for more details). To effectively use the deformable mirror in an adaptive optics application, the input beam must fill or overfill the active area of the deformable mirror (matching the 1/e² beam diameter to the pupil diameter is a common practice), and the defined pupil in the software for the wavefront sensor needs to be adjusted to match the pupil of the deformable mirror.

Click to Enlarge

Piezoelectric Deformable Mirror Structure

To construct the mirror assembly, a thin, UV-enhanced-aluminum-coated or protected-silver-coated glass disk is glued to a circular piezoceramic disk. The electrode attached to the back of the disk is divided into 40 single segments arranged in a circular keystone pattern. See the table above for a diagram of the keystone pattern, and the drawing to the left for a diagram of the mirror/piezoceramic disk/electrode structure. Each segment is controlled independently by applying a voltage between 0 and 200 V for the DMP40 series mirrors and 0 and 300 V for the DMH40 series mirrors. The surface is designed to be flat when 100 V for the DMP40 series DMs or 150 V for the DMH40 series DMs is applied across each electrode (see the graphs below).

In addition to the 40 actuators, the DMP40 series DMs have three arms attached to the edge of the piezoelectric disk. Applying a voltage to an arm will change the height of the mirror at the connection point. By using three identical arms, the mirror can be tilted in any direction within ±2 mrad. Applying the same voltage to each arm will move the mirror parallel to its surface while holding the tilt constant, which can be used for optical phase modulation.

While all piezoelectric deformable mirrors will experience hysteresis, the software package for these mirrors has been designed with integrated hysteresis compensation to help mitigate the effect.

The AOK8(/M) and AOKWT1(/M) AO Kits come with a high-stroke piezoelectric DM with Protected Silver (-P01) coating. The protected-silver-coated mirror is designed for use with light in the 450 nm to 20 µm range and has a 14.0 mm active area (pupil diameter). Custom kits are also available with mirrors that incorporate tip/tilt spiral arms or a UV-enhanced aluminum coating (see the Available Piezoelectric Deformable Mirrors Selection Guide above).

These deformable mirrors are also available separately. Click here for more information.

Click to Enlarge

Excel Spreadsheet with Raw Data for UV-Enhanced Aluminum Coating

The shaded region denotes the range over which we recommend using the UV-enhanced aluminum coating. Performance outside the shaded regions will vary from lot to lot and is not guaranteed, especially in out-of-band regions where the reflectance is fluctuating or sloped.

Click to Enlarge

Excel Spreadsheet with Raw Data for Protected Silver Coating

The shaded region denotes the range over which we recommend using the protected silver coating. Performance outside the shaded regions will vary from lot to lot and is not guaranteed, especially in out-of-band regions where the reflectance is fluctuating or sloped.

Click to Enlarge

This graph shows a typical hysteresis curve for a DMP40 mirror undergoing spherical deformation as the voltage across all 40 mirror segments is cycled between 0 and 200 V. The hysteresis is indicated by the black line in the graph above.

Click to Enlarge

This graph shows a typical hysteresis curve for a DMH40 mirror undergoing spherical deformation as the voltage across all 40 mirror segments is cycled between 0 and 300 V. The hysteresis is indicated by the black line in the graph above.

WFS

Click to Enlarge

A WFS20-5C High-Speed CMOS Wavefront Sensor with λ/100 sensitivity is included in each of our adaptive optics kits.

Shack-Hartmann Wavefront Sensors

- High-Speed CMOS-Based Wavefront Sensors Available

- Wavelength Range: 300 - 1100 nm or 400 - 900 nm

- Real-Time Wavefront and Intensity Distribution Measurements

- Nearly Diffraction-Limited Spot Size

- For CW and Pulsed Light Sources

- Flexible Data Export Options (Text or Excel)

- Live Data Readout via TCP/IP

Thorlabs' Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensors provide accurate measurements of the wavefront shape and intensity distribution of incident beams. Each wavefront sensor includes a CMOS-based sensor head and a microlens array (MLA). When incorporated in an adaptive optics (AO) kit, the sensor can detect distortions in the wavefront that can then be corrected by the deformable mirror. As summarized in the table below, we currently offer high-speed wavefront sensors along with three MLA options with different lenslet pitches and focal lengths which, when combined with the choice of sensor head, support optimal accuracy and wavefront dynamic ranges for a variety of applications.

Each of the AO kits offered below includes the WFS20-5C(/M) high-speed CMOS-based Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor. This wavefront sensor operates at frame rates as high as 880 Hz and has a wavefront sensitivity of up to λ/100 RMS (5.0 µm pixel pitch). For custom kits incorporating our other wavefront sensors (see the table below for a summary of options), please contact Tech Support.

Thorlabs' CMOS-Based wavefront sensors are also available separately.

| Shack-Hartmann Wavefront Sensor Selection Guidea | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item # Prefix (Sensor Head) |

Type | Item # Suffix (MLA) |

Mask or Coating (Wavelength) |

Lenslet Pitch |

Frame Rate | Effective Focal Lengthb |

Wavefront Accuracyc |

Wavefront Sensitivityd |

Wavefront Dynamic Rangee |

| WFS20 | High Speed | -5C | Chrome Mask (300 - 1100 nm) | 150 µm | 23 - 880 fps | 4.1 mm | λ/30 RMS | λ/100 RMS | >100λf |

| -7AR | AR Coating (400 - 900 nm) | 150 µm | 23 - 880 fps | 5.2 mm | λ/30 RMS | λ/100 RMS | >100λf | ||

| -14AR | AR Coating (400 - 900 nm) | 300 µm | 28 - 1120 fps | 14.6 mm | λ/60 RMS | λ/200 RMS | >50λf | ||

SOFTWARE

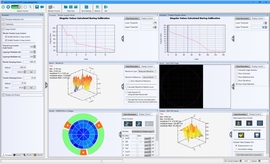

Click to Enlarge

Software GUI

Application Software

For out-of-the-box operation, the AO Kit comes with a fully functional stand-alone program for immediate operation of the instrument. The program is compatible with Windows® 7, 8, or 10. This software is capable of minimizing wavefront aberrations by analyzing the signals from the Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor and generating a voltage set that is applied to the deformable mirror. Users can also monitor the deformable mirror actuator control voltages, wavefront corrections, and intensity distribution in real time. Since the application software provides full control of the AO Kit, it is an excellent tool for research and development or developing educational packages based on adaptive optics. A software development kit is also included for custom applications (see below).

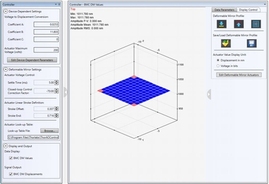

Click to Enlarge

MEMS-Based Deformable Mirror Control

Click to Enlarge

MEMS-Based Deformable Mirror Control

Deformable Mirror Control

MEMS-Based DMs

- Real-Time Representation of the Deformable Mirror Actuator Displacements (Based on Voltages Applied to the Mirror)

- Spreadsheet-Like Numerical Interface Provides User-Input of Actuator Deflections

- Save/Recall Mirror Surface Maps

The deformable mirror control for MEMS-based DMs shows a graphical plot of the DM surface shape as well a spreadsheet-like numerical interface that allows the user to input actuator deflections (in nanometers). The actuator deflection values may be changed individually or in selected groups. The actual shape of the DM will differ slightly due to a small influence of adjacent actuators.

Specific mirror shapes can be loaded and saved from this window, allowing the creation of a library of unique and specialized mirror shapes that can be later recalled at the click of a button.

Click to Enlarge

Piezoelectric Deformable Mirror Control

Piezoelectric DMs

- GUI Interface to View and Control Mirror Deformation

- Control Voltage of Individual Segments or Apply Zernike Terms to Entire Mirror Surface

- Tip/Tilt Control of Mirror Surface

The deformable mirror control window for piezoelectric DMs is laid out in five sections. The main section provides a graphical display of the mirror segments and arms, color-coded for the applied voltage. The 40 bimorph piezoelectric actuators of these mirrors are arranged in a radial pattern to allow the application of Zernike-based shapes to the mirror surface. The sidebar on the right of the screen allows Zernike terms Z4 through Z15 to be individually applied and controlled. Above the schematic of the DM actuators, the Segment Control section allows the voltage of individual mirror segments to be adjusted. Finally, these mirrors also feature three bimorph spiral arms attached to the edge of the main mirror disk to provide tip/tilt control of the entire mirror surface. The Tip/Tilt controls allow the user to adjust these settings.

Click to Enlarge

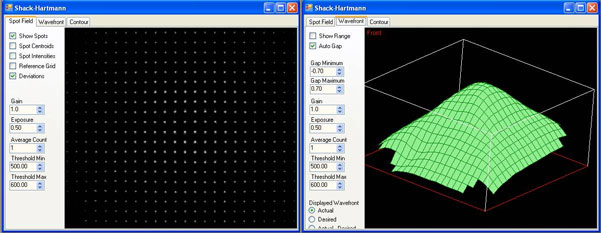

Shack-Hartmann Spot Field

Shack-Hartmann Control

- Four Tab Displays

- Wavefront Sensor Spot Field Measured Directly from the Sensor

- Wavefront Plot (See Example at Right)

- Contour Wavefront Plot

- Measured Zernike Coefficients

- Wavefront Plot is Scalable / Rotatable

- Easily Access Wavefront Sensor and Display Control Settings in Each Tab Display

- Display Measured, Reference, or Difference Wavefront Plots

- Min/Max Threshold Eliminates 'Flickering' Active/InactiveWFS Spots

- User-Controllable Spot Centroid and Reference Spot Indicators (See Example to the Right)

In the spot field window (far right image), the camera’s exposure time and gain can be controlled. A pupil control allows the user to analyze the wavefront data within a user-defined circular pupil. The camera image of the spots (white spots), spot centroid locations (red X’s), reference locations (yellow X’s), deviations (white lines between red and yellow X’s), and intensity levels can be displayed in the spot field window, as shown in the images to the far right and the bottom right.

In addition to the camera controls mentioned above, when viewing the wavefront, the user has the option to display the measured wavefront, target (reference) wavefront, or the difference between these two wavefronts. The wavefront plot can be viewed at pre-defined angles or can be continuously adjusted by the user.

Click to Enlarge

Zernike Function Generator

Zernike Wavefront Function Generator

- User-Controllable Reference Wavefront

- User-Defined Zernike Sampling Pupil Size and Position

- User-Defined Reference Using First 36 Zernike Terms

- User-Captured Reference Wavefront

- 3D Surface Plot or 2D Contour Plot Display

The Wavefront Generator control enables the user to create a reference wavefront by combining the first 36 Zernike polynomials in the spreadsheet-like grid. A graphical display of the created wavefront, along with the minimum, maximum, and peak-to-peak wavefront deviations are provided.

The wavefront generator control window also allows the user to capture the current measured wavefront and set it as the reference wavefront. Reference wavefronts can be saved and later recalled by the user.

Software Development Kit

The Adaptive Optics Kit includes a Software Development Kit (SDK) in the form of a flexible, cross-platform-compatible Dynamic Link Library (DLL) as well as full-featured Windows application software with an easy-to-use Graphical User Interface (GUI) for full system control right out of the box. The SDK is designed to be a conduit for easy integration of AO instrumentation, control, and arithmetic functions into a user system, making it ideal for research, development, and education applications. The application software provides immediate interaction with the AO Kit Deformable Mirror and Shack-Hartmann Wavefront Sensor and provides pop-up tooltips containing detailed information pertaining to specific function calls dispatched by the associated GUI control.

SDK Memory Management

A unique aspect of the SDK is its versatile memory structure. We provide an SDK that is compatible with a broad range of programming environments, including C-based languages, Visual Basic, LabVIEW, and any other language capable of interfacing with standard DLLs. These languages allocate data memory using different methods. In order to maximize performance and cross-platform compatibiity, the SDK employs a flexible memory structure that allows it to transparently use either its own or user software-allocated data space.

CONSTRUCTION

Figure 2. Schematic showing the major components included with the Dual-DM Adaptive Optics Kit (Item # AOKWT1(/M)). L, M, DM, BS, and BD refer to lens, mirror, deformable mirror, beamsplitter, and beam dump, respectively. The "X" marks the position of the cage system U-bench, which is also the location of an image plane in the setup; if desired, a user-supplied sample can be inserted at this location.

Figure 1. Schematic showing the major components included with the Single-DM Adaptive Optics Kits (Item #s AOK5(/M) and AOK8(/M)). L, M, DM, BS, and BD refer to lens, mirror, deformable mirror, beamsplitter, and beam dump, respectively. The "X" marks the position of the cage system U-bench, which is also the location of an image plane in the setup; if desired, a user-supplied sample can be inserted at this location.

Figure 3. A photograph of an AOK5 Adaptive Optics Kit. Please note that the breadboard is not included with the purchase of an AO kit. The key components discussed in the text to the left are numbered.

Figure 4. A photograph of an AOKWT1 Woofer-Tweeter Adaptive Optics Kit. Please note that the breadboard is not included with the purchase of an AO kit. The key components discussed in the text to the left are numbered.

AO Kit Construction

These adaptive optics (AO) kits come with a WFS20-5C High-Speed CMOS Shack-Hartmann Wavefront Sensor (WFS), one or two deformable mirrors (DMs), and control software (Windows 7, 8, and 10 compatible). Additionally, these kits include a light source, all collimation/imaging optics, and all mounting hardware necessary to build the layouts depicted in Fig. 1 (single-DM configuration) and Fig. 2 (dual-DM configuration) to the right. Please note that a breadboard is not included. We recommend building the single-DM AO kits on an 18" x 24" (450 mm x 600 mm) breadboard such as the MB1824 (MB4560/M) and the dual-DM AO kit on a 24" x 24" (600 mm x 600 mm) breadboard such as the MB2424 (MB6060/M).

Fig. 3 shows an assembled AOK5 AO Kit, which is a single-DM configuration, while Fig. 4 shows the AOKWT1 Woofer-Tweeter kit, which is a dual-DM configuration. The AOK5(/M) and AOK8(/M) adaptive optics kits have the same basic structure but use different lenses and mirrors to account for the DM coating and input aperture. The AOKWT1(/M) kit has an additional section to account for the extra DM in the kit. The construction of the single-DM AOK5 AO kit and dual-DM AOKWT1 AO kit are described here, and the optics included in each kit are outlined in the table below. More combinations are available as specials.

If you are not familiar with Thorlabs' 30 mm cage assemblies, they consist of cage-compatible components that are interconnected with Ø6 mm cage rods. This design ensures that the optical components housed inside the cage system have a common optical axis.

Single-DM Kit Construction

These single-DM kits include three pre-aligned sections that need to be arranged on a user-supplied breadboard. There are two sections of preassembled cage components that are used together to image a beam waist onto the DM surface and a third preassembled cage system is used to image a beam waist onto the Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor.

The first preassembled cage section of the AOK5(/M) kit consists of the laser diode source, one 50 mm focal length lens, one 75 mm focal length lens, two turning mirrors, and a U-shaped bench. The 635 nm Laser Diode Module, which outputs ~0.3 mW of light at 635 nm, is housed inside a CP33 Cage Plate (labeled as #1 in Fig. 3). Light exiting the module is directed through a LA1131-B 50 mm focal length lens housed in the CXY1A Translating Lens Mount (#2 in Fig. 3). The light then passes through two KCB1 Right-Angle Cage-Compatible Kinematic Mounts (the first of which is labeled as #3 in Fig. 3), which house PF10-03-P01 Protected Silver Mirrors; these mirrors offer an average reflectance of >97% from 450 nm to 2 µm and >95% from 2 to 20 µm. Then an LA1608-B 75 mm focal length lens housed in a CP33 Cage Plate (#4 in Fig. 3) images a beam waist to the center of the CBB1(/M) 30 mm Cage System U-Bench (represented by an X in Fig. 1 and labeled as #5 in Fig. 3 to the right). A sample can be placed in this image plane. This subassembly in the AOK8(/M) is configured similarly, but the lenses have focal lengths of 30 mm and 100 mm.

The second preassembled cage section uses two more LA1608-B 75 mm focal length lenses (one is housed in the CP33 mount labeled as #6 and the other in the CXY1A mount labeled as #7 in Fig. 3) to image a beam waist onto the DM (#8); by having a beam waist at the DM surface, the range of actuation needed to correct for any aberrations is minimized. The second subassembly is similar in the AOK8(/M) kit, except that 75 mm and 150 mm focal length lenses are used.

The DM reflects the beam through a shallow angle of ~35° into the third preassembled cage section. This section of the AOK5(/M) kit contains two more 75 mm focal length lenses, which are once again housed using a CP33 Cage Plate (#9 in Fig. 3) and CXY1A Translating Lens Mount (#10 in Fig. 3). In the AOK8(/M) kit, one 60 mm focal length lens and one 175 mm focal length lens are used. These lenses are used to place the DM in a plane that is conjugate with the Shack-Hartmann lenslet array, thereby relaying the image on the DM to the WFS. This provides the software with image information used to not just observe the wavefront but effectively optimize the DM actuator positions when running in closed-loop operation.

After exiting the third cage subassembly, a BP108 8:92 (R:T) pellicle beamsplitter (#11 in Fig. 3) is used to direct a small portion of the light to the last major component of the AO kit, the Shack-Hartmann WFS (#12). The portion of light transmitted by the beamsplitter can be blocked by a beam block (#13) that is constructed from an SM1A7 Alignment Blank. Alternatively, the beam block can be removed and the light can be launched into an application.

Dual-DM Kit Construction

The cage components are divided into four pre-aligned pieces that need to be arranged on a user-supplied breadboard. There are two sections of preassembled cage components that are used together to image a beam waist onto the first DM surface, a third section that images the light onto the second DM, and a fourth preassembled cage system is used to image a beam waist onto the Shack-Hartmann WFS.

The first two preassembled cage sections of the AOKWT1(/M) kit consist of the laser diode source, four lenses, two turning mirrors, and a U-shaped bench. The 635 nm Laser Diode Module, which outputs ~0.3 mW of light at 635 nm, is housed inside a CP33 Cage Plate (labeled as #1 in Fig. 4). Light exiting the module is focused by a LA1289-B 30 mm focal length lens housed in the CXY1A Translating Lens Mount (#2 in Fig. 4). The light then passes through two KCB1 Right-Angle Cage-Compatible Kinematic Mounts (the first of which is labeled as #3 in Fig. 4), which house PF10-03-P01 Protected Silver Mirrors; these mirrors offer an average reflectance of >97% from 450 nm to 2 µm and >95% from 2 to 20 µm.

The AOKWT1 kit uses an LA1509-B 100 mm focal length lens housed in the CP33 Cage Plate (#4 in Fig. 4) to image a beam waist at the center of the CBB1(/M) 30 mm Cage System U-Bench (represented by an X in Fig. 2 and labeled as #5 in Fig. 4 to the right). A sample can be placed in this image plane. Then, two more lenses (LA1608-B 75 mm and LA1433-B 150 mm focal length lenses, both of which are housed in the CP33 mounts labeled as #6 and #7 in the figure) are used to image a beam waist onto the first DM (#8), acting as a woofer correcting for lower order aberrations. By having a beam waist at the DM surface, the range of actuation needed to correct for any aberrations is minimized.

The first DM reflects the beam through a shallow angle of ~30° into the third preassembled cage section. This section contains a LA1708-B 200 mm focal length lens housed using a CXY1A Translating Lens Mount (#9 in Fig. 4) and a LA1134-B 60 mm focal length lens in a CP33 Cage Plate (#10 in Fig. 4). The lenses image a beam waist onto the second DM (#11), which acts as the tweeter of the system correcting the higher order aberrations.

The second DM reflects the beam through another shallow angle of ~40° into the fourth preassembled cage section. This section contains two LA1608-B 75 mm focal length lenses, which are once again housed in two CP33 Cage Plates (#12 and #13). These lenses are used to place the DM in a plane that is conjugate with the Shack-Hartmann lenslet array, thereby relaying the image on the DM to the WFS. This provides the software with image information used to not just observe the wavefront but effectively optimize the DM actuator positions when running in closed-loop operation.

After exiting the third cage subassembly, a BSN10 10:90 (R:T) UVFS Plate Beamsplitter (#14 in Fig. 4) is used to direct a small portion of the light to the last major component of the AO kit, the Shack-Hartmann WFS (#15). The portion of light transmitted by the beamsplitter can be blocked by a beam block (#16) that is constructed from an SM1A7 Alignment Blank. Alternatively, the beam block can be removed and the light can be launched into an application.

A Note about the Optics Included with the Adaptive Optics Kits:

The AOK5(/M) and AOK8(/M) adaptive optics kits include similar optical and mechanical components. The optics that vary between the kits are described in the table below. The AOK8(/M) kit also uses longer beam expander sections than the AOK5(/M) kit to accommodate the larger entrance pupil of the piezoelectric deformable mirror. The AOKWT1(/M) kit includes both the MEMS and piezoelectric DM. A complete list of components included in each kit are outlined in the table on the Components tab, which is set up to highlight the similarities and differences between the kits.

| Wavelength-Dependent Components Included with Each AO Kita | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item # | Wavefront Sensor | Deformable Mirror | Lenses (Qty.) | Mirrors (Qty.) | Beamsplitter (Qty.) | Neutral Density Filters (Qty.) |

| AOK5(/M) | WFS20-5C(/M) | DM140A-35-P01 | LA1131-B (1) LA1608-B (5) |

PF10-03-P01 (2) | BP108 (1) | NE10A (1) NE20A (1) |

| AOK8(/M) | WFS20-5C(/M) | DMH40-P01 (DMH40/M-P01) |

LA1134-B (1) LA1229-B (1) LA1289-B (1) LA1433-B (1) LA1509-B (1) LA1608-B (1) |

PF10-03-P01 (2) | BP108 (1) | NE10A (1) NE20A (1) |

| AOKWT1(/M) | WFS20-5C(/M) | DM140A-35-P01 and DMH40-P01 (DMH40/M-P01) |

LA1134-B (1) LA1289-B (1) LA1433-B (1) LA1509-B (1) LA1608-B (3) LA1708-B (1) |

PF10-03-P01 (2) | BSN10 (1) | NE10A (1) NE20A (1) |

COMPONENTS

| AO Kit Components | ||

|---|---|---|

| AOK5(/M) | AOK8(/M) | AOKWT1(/M) |

Click for Details |

Click for Details |

Click for Details |

| Wavefront Sensor |

|---|

| Deformable Mirror(s) |

|---|

| Light Source |

|---|

| Optics |

|---|

| Mechanics |

|---|

| Alignment Tools |

|---|

AO TUTORIAL

Introduction:

Adaptive optics (AO) is a rapidly growing multidisciplinary field encompassing physics, chemistry, electronics, and computer science. AO systems are used to correct (shape) the wavefront of a beam of light. Historically, these systems have their roots in the international astronomy and US defense communities. Astronomers realized that if they could compensate for the aberrations caused by atmospheric turbulence, they would be able to generate high resolution astronomical images; with sharper images comes an additional gain in contrast, which is also advantageous for astronomers since it means that they can detect fainter objects that would otherwise go unnoticed. While astronomers were trying to overcome the blurring effects of atmospheric turbulence, defense contractors were interested in ensuring that photons from their high-power lasers would be correctly pointed so as to destroy strategic targets. More recently, due to advancements in the sophistication and simplicity of AO components, researchers have utilized these systems to make breakthroughs in the areas of femtosecond pulse shaping, microscopy, laser communication, vision correction, and retinal imaging. Although dramatically different fields, all of these areas benefit from an AO system due to undesirable time-varying effects.

Typically, an AO system is comprised from three components: (1) a wavefront sensor, which measures these wavefront deviations, (2) a deformable mirror, which can change shape in order to modify a highly distorted optical wavefront, and (3) real-time control software, which uses the information collected by the wavefront sensor to calculate the appropriate shape that the deformable mirror should assume in order to compensate for the distorted wavefront. Together, these three components operate in a closed-loop fashion. By this, we mean that any changes caused by the AO system can also be detected by that system. In principle, this closed-loop system is fundamentally simple; it measures the phase as a function of the position of the optical wavefront under consideration, determines its aberration, computes a correction, reshapes the deformable mirror, observes the consequence of that correction, and then repeats this process over and over again as necessary if the phase aberration varies with time. Via this procedure, the AO system is able to improve optical resolution of an image by removing aberrations from the wavefront of the light being imaged.

The Wavefront Sensor:

The role of the wavefront sensor in an adaptive optics system is to measure the wavefront deviations from a reference wavefront. There are three basic configurations of wavefront sensors available: Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensors, shearing interferometers, and curvature sensors. Each has its own advantages in terms of noise, accuracy, sensitivity, and ease of interfacing it with the control software and deformable mirror. Of these, the Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor has been the most widely used.

A Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor uses a lenslet array to divide an incoming beam into a bunch of smaller beams, each of which is imaged onto a CCD camera, which is placed at the focal plane of the lenslet array. If a uniform plane wave is incident on a Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor (refer to Fig. 1), a focused spot is formed along the optical axis of each lenslet, yielding a regularly spaced grid of spots in the focal plane. However, if a distorted wavefront (i.e., any non-flat wavefront) is used, the focal spots will be displaced from the optical axis of each lenslet. The amount of shift of each spot’s centroid is proportional to the local slope (i.e., tilt) of the wavefront at the location of that lenslet. The wavefront phase can then be reconstructed (within a constant) from the spot displacement information obtained (see Fig. 2).

Figure 1. When a planar wavefront is incident on the Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor's microlens array, the light imaged on the CCD sensor will display a regularly spaced grid of spots. If, however, the wavefront is aberrated, individual spots will be displaced from the optical axis of each lenslet; if the displacement is large enough, the image spot may even appear to be missing. This information is used to calculate the shape of the wavefront that was incident on the microlens array.

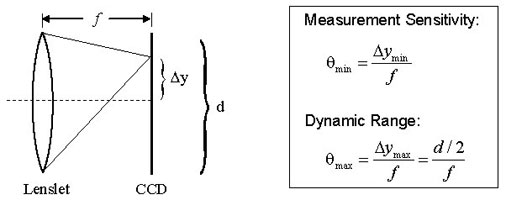

Figure 2. Two Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor screen captures are shown: the spot field (left-hand frame) and the calculated wavefront based on that spot field information (right-hand frame).

Figure 3. Dynamic range and measurement sensitivity are competing properties of a Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor. Here, f, Δy, and d represent the focal length of the lenslet, the spot displacement, and the lenslet diameter, respectively. The equations provided for the measurement sensitivity θ min and the dynamic range θmax are obtained using the small angle approximation. θmin is the minimum wavefront slope that can be measured by the wavefront sensor. The minimum detectable spot displacement Δymin depends on the pixel size of the photodetector, the accuracy of the centroid algorithm, and the signal to noise ratio of the sensor. θmax is the maximum wavefront slope that can be measured by the wavefront sensor and corresponds to a spot displacement of Δymax, which is equal to half of the lenslet diameter. Therefore, increasing the sensitivity will decrease the dynamic range and vice versa.

The four parameters that greatly affect the performance of a given Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor are the number of lenslets (or lenslet diameter, which typically ranges from ~100 – 600 μm), dynamic range, measurement sensitivity, and the focal length of the lenslet array (typical values range from a few millimeters to about 30 mm). The number of lenslets restricts the maximum number of Zernike coefficients that a reconstruction algorithm can reliably calculate; studies have found that the maximum number of coefficients that can be used to represent the original wavefront is approximately the same as the number of lenslets. When selecting the number of lenslets needed, one must take into account the amount of distortion s/he is trying to model (i.e., how many Zernike coefficients are needed to effectively represent the true wave aberration). When it comes to measurement sensitivity θmin and dynamic range θmax, these are competing specifications (see Fig. 3 to the right). The former determines the minimum phase that can be detected while the latter determines the maximum phase that can be measured.

A Shack-Hartmann sensor’s measurement accuracy (i.e., the minimum wavefront slope that can be measured reliably) depends on its ability to precisely measure the displacement of a focused spot with respect to a reference position, which is located along the optical axis of the lenslet. A conventional algorithm will fail to determine the correct centroid of a spot if it partially overlaps another spot or if the focal spot of a lenslet falls outside of the area of the sensor assigned to detect it (i.e., spot crossover). Special algorithms can be implemented to overcome these problems, but they limit the dynamic range of the sensor (i.e., the maximum wavefront slope that can be measured reliably). The dynamic range of a system can be increased by using a lenslet with either a larger diameter or a shorter focal length. However, the lenslet diameter is tied to the needed number of Zernike coefficients; therefore, the only other way to increase the dynamic range is to shorten the focal length of the lenslet, but this in turn, decreases the measurement sensitivity. Ideally, choose the longest focal length lens that meets both the dynamic range and measurement sensitivity requirements.

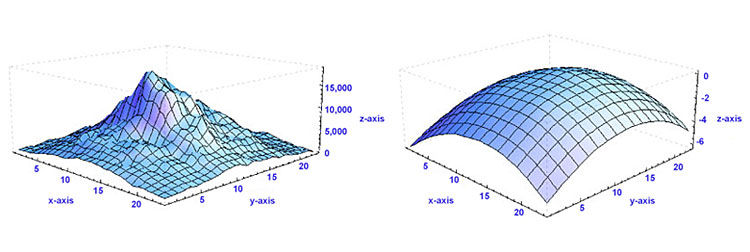

The Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor is capable of providing information about the intensity profile as well as the calculated wavefront. Be careful not to confuse these. The left-hand frame of Fig. 4 shows a sample intensity profile, whereas the right-hand frame shows the corresponding wavefront profile. It is possible to obtain the same intensity profile from various wavefunction distributions.

Figure 4. Several pieces of information are provided by the Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor, including information about the total power at each lenslet and the calculated wavefront distribution present. Here, the left-hand frame shows a sample intensity profile, while the right-hand frame shows the corresponding wavefront.

The Deformable Mirror:

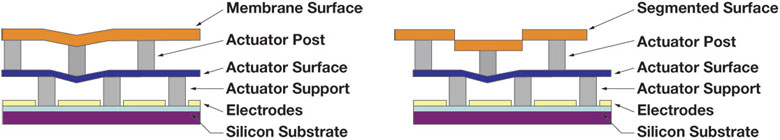

The deformable mirror (DM) changes shape in response to position commands in order to compensate for the aberrations measured by the Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor (refer to the Aberrations tab to learn more about the aberrations that the DM can correct). Ideally, it will assume a surface shape that is conjugate to the aberration profile (see Fig. 5). In many cases, the surface profile is controlled by an underlying array of actuators that move in and out in response to an applied voltage. Deformable mirrors come in several different varieties, but the two most popular categories are segmented and continuous (see Fig. 6). Segmented mirrors are comprised from individual flat segments that can either move up and down (if each segment is controlled by just one actuator) or have tip, tilt, and piston motion (if each segment is controlled by three actuators). These mirrors are typically used in holography and for spatial light modulators. Advantages of this configuration include the ability to manufacture the segments to tight tolerances, the elimination of coupling between adjacent segments of the DM since each acts independently, and the number of degrees of freedom per segment. However, on the down side, the regularly spaced gaps between the segments act like a diffraction pattern, thereby introducing diffractive modes into the beam. In addition, segmented mirrors require more actuators than continuous mirrors to compensate for a given incoming distorted wavefront. To address the optical problems with segmented DMs, continuous faceplate DMs (such as those included in our AO Kits) were fabricated. They offer a higher fill factor (i.e., the percentage of the mirror that is actually reflective) than their segmented counterparts. However, their drawback is that the actuators are mechanically coupled. Therefore, when one actuator moves, there is some finite response along the entire surface of the mirror. The 2D shape of the surface caused by displacing one actuator is called the influence function for that actuator. Typically, adjacent actuators of a continuous DM are displaced by 10-20% of the actuation height; this percentage is known as the actuator coupling. Note that segmented DMs exhibit zero coupling but that isn’t necessarily desirable.

Figure 5. The aberration compensation capabilities of a flat and MEMS deformable mirror are compared. (a) If an unaberrated wavefront is incident on a flat mirror surface, the reflected wavefront will remain unaberrated. (b) A flat mirror is not able to compensate for any deformations in the wavefront; therefore, an incoming highly aberrated wavefront will retain its aberrations upon reflection. (c) A MEMS deformable mirror is able to modify its surface profile to compensate for aberrations; the DM assumes the appropriate conjugate shape to modify the highly aberrated incident wavefront so that it is unaberrated upon reflection.

Figure 6. Cross sectional schematics of the main components of BMC's continuous (left) and segmented (right) MEMS deformable mirrors.

The range of wavefronts that can be corrected by a particular DM is limited by the actuator stroke and resolution, the number and distribution of actuators, and the model used to determine the appropriate control signals for the DM; the first two are physical limitations of the DM itself, whereas the last one is a limitation of the control software. The actuator stroke is another term for the dynamic range (i.e., the maximum displacement) of the DM actuators and is typically measured in microns. Inadequate actuator stroke leads to poor performance and can prevent the convergence of the control loop. The number of actuators determines the number of degrees of freedom that the mirror can correct for. Although many different actuator arrays have been proposed, including square, triangular, and hexagonal, most DMs are built with square actuator arrays, which are easy to position on a Cartesian coordinate system and map easily to the square detector arrays on the wavefront sensors. To fit the square array on a circular aperture, the corner actuators are sometimes removed. Although more actuators can be placed within a given area using some of the other configurations, the additional fabrication complexity usually does not warrant that choice.

Figure 7. A cross-like pattern is created on the DM surface by applying the voltages necessary for maximum deflection of the 44 actuators that comprise the middle two rows and middle two columns of the array. The frame on the left shows a screen shot of the AO kit software depicting the DM surface, whereas the frame on the right, which was obtained through quasi-dark field illumination, shows the actual DM surface when programmed to these settings. Note that the white light source used for illumination is visible in the lower right-hand corner of the photograph.

Figure 7 (left frame) shows a screen shot of a cross formed on the 12 x 12 actuator array of the DM included with the adaptive optics kit. To create this screen shot, the voltages applied to the middle two rows and middle two columns of actuators were set to cause full deflection of the mirror membrane. In addition to the software screen shot depicting the DM surface, quasi-dark field illumination was used to obtain a photograph of the actual DM surface when programmed to these settings (see Fig. 7, right frame)

The Control Software:

In an adaptive optics setup, the control software is the vital link between the wavefront sensor and the deformable mirror. It converts the wavefront sensor’s electrical signals, which are proportional to the slope of the wavefront, into compensating voltage commands that are sent to each actuator of the DM. The closed-loop bandwidth of the adaptive optics system is directly related to the speed and accuracy with which this computation is done, but in general, these calculations must occur on a shorter time scale than the aberration fluctuations.

In essence, the control software uses the spot field deviations to reconstructs the phase of the beam (in this case, using Zernike polynomials) and then sends conjugate commands to the DM. A least-squares fitting routine is applied to the calculated wavefront phase in order to determine the effective Zernike polynomial data outputted for the end user. Although not the only form possible, Zernike polynomials provide a unique and convenient way to describe the phase of a beam. These polynomials form an orthogonal basis set over a unit circle with different terms representing the amount of focus, tilt, astigmatism, comma, et cetera; the polynomials are normalized so that the maximum of each term (except the piston term) is +1, the minimum is –1, and the average over the surface is always zero. Furthermore, no two aberrations ever add up to a third, thereby leaving no doubt about the type of aberration that is present.

ABERRATIONS

Monochromatic Aberrations

There are five primary monochromatic aberrations, which can be further divided into two subgroups: those that deteriorate the image (spherical aberration, coma, and astigmatism) and those that deform the image (field curvature and distortion). These aberrations are a direct result of departures from first-order (i.e., sinθ≈θ) theory, which assumes the light rays make small angles with the principal axis. As soon as one wants to consider light rays incident on the periphery of a lens, the statement sinθ≈θ, which forms the basis of paraxial optics, is no longer satisfactory and one must consider more terms in the expansion:

The five primary monochromatic aberrations were first studied by Ludwig von Seidel, and hence, they are frequently referred to as the Seidel aberrations. Please note that since the expansion of sinθ is an infinite sum, the five monochromatic aberrations discussed below are not the only ones possible; there are additional higher-order aberrations that make smaller contributions to image degradation. The surface of the deformable mirror can be altered to accommodate all of these types of monochromatic aberrations.

1) Spherical Aberrations

For parallel incoming light rays, an ideal lens will be able to focus the rays to a point on the optical axis as shown in Fig. 1a; consequently, under ideal circumstances, the image of a point source that is located on the optical axis will be a bright circular disk surrounded by faint rings (see the Airy diffraction pattern shown in Fig. 1b). However, in reality, the light rays that strike a spherical converging lens far from the principal axis will be focused to a point that is closer to the lens than those light rays that strike the spherical lens near the principal axis (see Fig. 1c). Consequently, there is no single focus for a spherical lens, and the image will appear to be blurred; instead of having an Airy diffraction pattern in which nearly all the light is contained in a central bright circular spot, spherical aberration will redistribute some of the light from the central disk to the surrounding rings (see Fig. 1d), thereby reducing image contrast. Whenever spherical aberration is present, the best focus for an uncorrected lens will be somewhere between the focal planes of the peripheral and axial rays. Please note that spherical aberration only pertains to object points that are located on the optical axis.

Figure 1. Comparison of an ideal situation to one in which spherical aberration is present. (a) For a perfect lens, all incoming light rays get focused to a single point. (b) The Airy diffraction pattern corresponding to a point source that has been imaged by a perfect lens consists of a bright central spot surrounded by faint concentric rings. (c) For a real lens, light incident on the edges of a lens is refracted more than the light striking the center of the lens, and thus, there is not one unique focal point for all incident light rays. (d) Spherical aberration degrades resolution by redistributing some of the light from the central bright spot to the surrounding concentric rings.

2) Coma

Coma, or comatic aberration, is an image-degrading aberration associated with object points that are even slightly off axis. When an off-axis bundle of light is incident on a lens, the light will undergo different amounts of refraction depending on where it strikes the lens (see Fig. 2a); as a result, each annulus of light will focus onto the image plane at a slightly different height and with a different spot size (see Fig. 2b), thereby leading to different transverse magnifications. The resulting image of a point source, which is shown in Fig. 2c, is a complicated asymmetrical diffraction pattern with a bright central core and a triangular flare that departs drastically from the classical Airy pattern shown in Fig 1b above. The elongated comet-like structure from which this type of aberration takes its name can extend either towards or away from the optical axis depending on whether the comatic aberration is negative or positive, respectively. Due to the asymmetry that coma causes in images, many consider it to be the worst type of aberration.

Figure 2. The effects of positive coma are shown. (a) When a light source is off-axis, the various portions of the lens do not refract the light to the same point on the image plane. (b) The central region of the lens forms a point image at the vertex of the cone, while larger rings on the periphery of the lens correspond to larger comatic circles that are displaced farther from the principal axis. (c) Coma leads to a complicated asymmetrical comet-like diffraction pattern characterized by an elongated structure of blotches and arcs. Note that the diffraction pattern shown assumes no spherical aberration.

3) Astigmatism

Astigmatism, like coma, is an aberration that arises when an object point is moved away from the optical axis. Under such conditions, the incident cone of light will strike the lens obliquely, leading to a refracted wavefront characterized by two principal curvatures that ultimately determine two different focal image points. Figure 3a shows the two planes one needs to consider: the tangential (also known as the meridional) plane and the sagittal plane; the tangential plane is defined by the chief ray (i.e., the light ray from the object that passes through the center of the lens) and the optical axis, while the sagittal plane is a plane that contains the chief ray and is perpendicular to the tangential plane. In addition to the chief light ray, Fig. 3a also shows two other off-axis light rays, one passing through the tangential plane and the other passing through the sagittal plane. For complex multi-element lens systems (e.g., microscope objective or ASOM system), the tangential plane remains coherent from one end of the system to the other while the sagittal plane usually changes slope as the chief ray’s propagation direction is altered by the various components in the lens system. Consequently, in general, the focal lengths associated with these planes will be different (see Fig. 3b). If the sagittal focus and the tangential focal points are coincident, then the object point is on axis and the lens is free of astigmatism. However, as the amount of astigmatism present increases, the distance between these two foci will also increase, and as a result, the image will lose definition around its edges. The presence of astigmatism will cause the ideal circular point image to be blurred into a complicated elongated diffraction pattern that appears more linelike when more astigmatism is present (see Figs. 3c and 3d).

Figure 3. The effects of astigmatism, assuming the absence of spherical aberration and coma, are illustrated. (a) The tangential and sagittal planes are shown. (b) Light rays in the tangential and sagittal planes are refracted differently, ultimately leading to two different focal planes, which are labeled as the tangential focus and sagittal focus. (c) The Airy diffraction pattern of a point source as viewed at the tangential focal plane. (d) The Airy diffraction pattern of a point source as viewed at the sagittal focal plane.

4) Field Curvature

For most optical systems, the final image must be formed on a planar surface; however, in actuality, a lens that is free of all other off-axis aberrations creates an image on a curved surface known as a Petzval surface. This nominal curvature of this surface, which is known as the Petzval curvature, is the reciprocal of the lens radius. For a positive lens, this surface curves inward towards the object plane, whereas for a negative lens, the surface curves away from that plane. The field curvature aberration arises from forcing a naturally curved image surface into a flat one. For the image, the presence of field curvature makes it impossible to have both the edges and central region of the image be crisp simultaneously. If the focal plane is shifted to the vertex of the Petzval surface (Position A in Fig. 4), the central part of the image will be in focus while the outer portion of the image will be blurred, making it impossible to distinguish minor structural details in this outer region. Alternatively, if the image plane is moved to the edges of the Petzval surface (Position B in Fig. 4), the opposite effect occurs; the edges of the image will come into focus, but the central region will become blurred. The best compromise between these two extremes is to place the image plane somewhere in between the vertex and edges of the Petzval surface, but regardless of its location, the image will never appear sharp and crisp over the entire field of view.

Figure 4. Field curvature, an aberration associated with off-axis objects, arises because the best image is not formed on the paraxial image plane but on a parabolic surface called the Petzval surface. (a) Depending on the location of the focal plane along the optic axis, either the central (if at location A) or peripheral (if at location B) portions of the field of view will be in focus but not both. (b) The central portion of the image will be crisp if the image plane is located at position A. (c) The edges of the image will be sharply in focus if the image plane is located at position B.

5) Distortion

The last of the Seidel aberrations is distortion, which is easily recognized in the absence of all other monochromatic aberrations because it deforms the entire image even though each point is sharply focused. Distortion arises because different areas of the lens usually have different focal lengths and magnifications. If no distortion is present in a lens system, the image will be a true magnified reproduction of the object (see Fig. 5b). However, when distortion is present, off-axis points are imaged either at a distance greater than normal or less than normal, leading to a pincushion (see Fig. 5a) or barrel (see Fig. 5c) shape, respectively.

Figure 5. The effects of distortion, assuming the absence of all other forms of aberration, are illustrated. (a) Positive or pincushion distortion occurs when the transverse magnification of a lens increases with the axial distance; this effect causes each image point to be displaced radially outward from the center, with the most distant points undergoing the largest displacements. (b) If no distortion is present, the image will be a scaled duplicate of the object. (c) Negative or barrel distortion occurs when the transverse magnification of a lens decreases with axial distance; in this case, each image point moves radially inward toward the center; again, the most distant points undergo the largest displacements.

Chromatic Aberrations

The monochromatic aberrations discussed above can all be compensated for using a deformable mirror such as the one included in these adaptive optics kits. However, when a broadband light source is used, chromatic aberrations will result. Since a DM cannot compensate for these aberrations, we will only briefly mention them here. Chromatic aberrations, which come in two forms (i.e., lateral and longitudinal), arise from the variation of the index of refraction of a lens with incident wavelength. Since blue light is refracted more than red light, the lens is not capable of focusing all colors to the same focal point; therefore, the image size and focal point for each color will be slightly different, leading to an image that is surrounded by a halo. Generally, since the eye is most sensitive to the green part of the spectrum, the tendency is to focus the lens for that region; if the image plane is then moved towards (away from) the lens, the periphery of the blurred image will be tinted red (blue).

OFF-AXIS IMAGING

Introduction

Off-axis scanning is frequently used in many imaging techniques including Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT), Confocal Microscopy, and Adaptive Scanning Optical Microscopy (ASOM). Without adaptive optics, images obtained using these techniques will suffer from the off-axis aberrations discussed in the Aberrations tab, thereby requiring one to choose between resolution and field of view. However, by using a deformable mirror, this tradeoff is overcome. To learn more about how a deformable mirror works and its role in an adaptive optics system, please see the AO Tutorial tab.

Figure 1. (a) A schematic of Thorlabs' ASOM system, which consists of a custom-designed scan lens, a fast steering mirror, a 4.4 mm x 4.4 mm DM with a 12 x 12 grid of electrostatic actuators, and a CCD camera. (b) A photograph of the ASOM system.

An Example: ASOM

As an example, consider Thorlabs’ Adaptive Scanning Optical Microscope (ASOM), which is shown in Fig. 1 at the right and combines a high-speed steering mirror, large aperture scan lens, and micro-electro-mechanical (MEMS) deformable mirror to provide a large field of view (Ø40 mm) while preserving resolving power (1.5 μm over the entire field of view) and a high image acquisition rate (30 fps). As the imaged area on the sample is changed (by changing the orientation of the fast steering mirror), the deformable mirror is used to correct the off-axis aberrations introduced by the scan lens, thus maintaining the diffraction-limited 1.5 μm resolution across the extended composite field of view.

ASOM works by taking a sequence of small spatially separated images in rapid succession and then assembling them to form a large composite image. Although mosaic construction has been used in the past to expand the field of view while preserving resolution, it necessitated the use of a moving stage. In contrast, the ASOM uses a high speed 2D mirror, a specially designed scanner lens assembly, a deformable mirror, and additional imaging optics to overcome this tradeoff.

Figure 2 shows a schematic of the ASOM scanner lens assembly (SLA). Unlike a traditional microscope objective, which must image onto a flat surface, the ASOM allows for a curved image field (i.e., the natural image field shape for a lens – refer to the Field Curvature Section under the Aberrations tab), thereby greatly simplifying the optical design and number of lens elements necessary. The figure shows four different scan angle positions. The blue lines represent on-axis scanning, whereas the green, red, and yellow lines correspond to various off-axis scan angles. For each scan angle illustrated, the wavefront distortion as a function of linear displacement from the central position on the image tile of the wavefront sensor is given.

Figure 2. Adaptive Scanning Optical Microscopy (ASOM) utilizes a curved image field, thereby greatly simplifying the scanner lens assembly shown. The blue, green, red, and yellow rays represent various off-axis scan angles (0°, 2°, 4°, and 6°, respectively). For each angle, the corresponding wavefront distortion is shown. The graphs show the distortion (in waves) as a function of position on the wavefront sensor tile. Regardless of scan angle, notice that no waves of distortion are present at the exact center of each image tile. Please note that for this figure, the term "distortion" is meant to encompass all types of aberrations.

Although the large aperture scan lens and overall system layout are specifically designed to deal with field curvature, all other off-axis aberrations, such as coma and astigmatism (see the Aberrations tab for a detailed discussion), are still present in the ASOM system. These aberrations are compensated for at each individual field position throughout the scanner’s range by a deformable mirror. Figure 3 shows the optimal DM shape for a given angular position of the high speed steering mirror.

Figure 3. The angular position of the 2D steering mirror defines the observable field position. Here, the various mirror positions map out the image at five points along the y-axis. For each angular position of the high speed steering mirror shown in frame (a), the corresponding optimal deformable mirror shape is shown in frame (b). Note that the DM topology configuration necessary to correct the image at each field position is not trivial.

Figure 4. Resolution target imaged using (a) a flat mirror (b) an optimized deformable mirror. The smallest lines are separated by 2 μm.

The deformable mirror's impressive wavefront correction abilities are demonstrated in Fig. 4, which shows an air force target imaged using a flat mirror in frame (a) and a deformable mirror in frame (b). In frame (a), the image is completely blurred, making it impossible to distinguish any structure, whereas, in frame (b), the smallest lines, which are only separated by 2 μm, are now discernable.

PUBLICATIONS

Adaptive Optics Enhances Multiphoton Retinal Images

Featured Researchers: J. M. Bueno, E. J. Gualda, and P. Arta

Adaptive Optics and Deformable Mirror Publications

2019

Emily Finan; Thomas Milster; Young Sik Kim, “Adaptive optics correction using coherently illuminated diffractive optics,” Proc. SPIE 11125, Optical Engineering and Applications, 1112509 (August 30, 2019); doi: 10.1117/12.2530045.

Ming Zhang, Dun Li, Yu Ning, Xin Wang, and Fengjie Xi "Simulation and analysis of distortion correction of supercontinuum wavefront based on SPGD algorithm," Proc. SPIE 11046, Fifth International Symposium on Laser Interaction with Matter, 110460Y (March 29, 2019); doi: 10.1117/12.2524367.

Yide Zhang, Ian H. Guldner, Evan L. Nichols, David Benirschke, Cody J. Smith, Siyuan Zhang, and Scott S. Howard "Three-dimensional deep tissue multiphoton frequency-domain fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy via phase multiplexing and adaptive optics," Proc. SPIE 10882, Multiphoton Microscopy in the Biomedical Sciences XIX, 108822H (February 22, 2019); doi: 10.1117/12.2510674.

2018

Tracy T. Chow, Ziaoyu Shi, Jen=Hsuan Wei, Juan Guan, Guido Stadler, Bo Huang, and Elizabeth H. Blackburn, "Local enrichment of HP1alpha at telomeres alters their structure and regulation of telomere protection," Nature Commmunications, Vol. 9, 3583 (2018); doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05840-y.

Jamie Soon, François Rigaut, Ian Price, "CACAO: a generic low-cost adaptive optics system for small aperture telescopes," Proc. SPIE 10703, Adaptive Optics Systems VI, 107035Z (July 11, 2018); doi: 10.1117/12.2311823.

Andrey Aristov, Benoit Lelandais, Elena Rensen, and Christophe Zimmer, "ZOLA-3D allows flexible 3D localization microscopy over an adjustable axial range," Nature Communications, Vol. 9, 2409 (2018); doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04709-4.

2017

Boris Ayancán, Héctor González-Núñez, and Andrés Guesalaga, “A flexible AO system for research and educational purposes,” Óptica Pura y Aplicada, Vol. 50, Issue 4, pp. 389-399 (2017).

Thomas Milster; Young Sik Kim, “Adaptive optics for data recovery on optical disk fragments,” Proc. SPIE 10384, Optical Engineering and Applications, 103840J (September 20, 2017); doi:10.1117/12.2277078.

Moon-Seob Jin ; Ryan Luder ; Lucas Sanchez ; Michael Hart, “Control code for laboratory adaptive optics teaching system,” Proc. SPIE 10401, Astronomical Optics: Design, Manufacture, and Test of Space and

Ground Systems, 104011K (September 5, 2017); doi:10.1117/12.2276176.

Lucas Sanchez ; Moon-Seob Jin ; R. Phillip Scott ; Ryan Luder ; Michael Hart, “Voltage linear transformation circuit design,” Proc. SPIE 10401, Astronomical Optics: Design, Manufacture, and Test of Space and

Ground Systems, 1040115 (September 5, 2017); doi:10.1117/12.2276166.

Xiaoyu Shi, Galo Garcia III, Julie C. Van De Weghe, Ryan McGorty, Gregory J. Pazour, Dan Doherty, Bo Huang, and Jeremy F. Reiter, "Super-resolution microscopy reveals that disruption of ciliary transition-zone architecture causes Joubert syndrome," Nature Cell Biology, Vol. 9, pp. 1178 - 1188 (2017); doi: 10.1038/ncb3599.

2016

M. Ishizuka, T. Kotani, J. Nishikawa, M. Tamura, T. Kurokawa, T. Mori, and T. Kokubo "Fiber mode scrambler experiments for the Subaru Infrared Doppler Instrument (IRD)," Proc. SPIE 9912, Advances in Optical and Mechanical Technologies for Telescopes and Instrumentation II, 99121Q (August 12, 2016); doi: 10.1117/12.2232166.

2012

Jiangpei Dou ; Deqing Ren ; Yongtian Zhu ; Xi Zhang ; Rong Li, “A dark-hole correction test for the step-transmission filter based coronagraphic system,” Proc. SPIE 8442, Space Telescopes and Instrumentation 2012: Optical, Infrared, and Millimeter Wave, 84420D (September 21, 2012); doi:10.1117/12.924248.

R. Davies, M. Kasper, “Adaptive Optics for Astronomy,” arXiv:1201.5741v1 [astro-ph.IM].

Wei Sun, Yang Lu, Thomas G. Bifano, Jason B. Stewart, and Charles P. Lin, “Critical considerations of pupil alignment to achieve open-loop control of MEMS deformable mirror in nonlinear laser scanning fluorescence microscopy,” Proc. SPIE 8253, 82530H (2012); http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/12.909652.

Alexis Hill ; Steven Cornelissen ; Daren Dillon ; Charlie Lam ; Dave Palmer ; Les Saddlemyer, “Flexure mount for a MEMS deformable mirror for the Gemini Planet Imager,” Proc. SPIE 8450, Modern Technologies in Space- and Ground-based Telescopes and Instrumentation II, 84500H (September 13, 2012); doi:10.1117/12.926842.

Katie M. Morzinski, Andrew P. Norton, Julia Wilhelmson Evans, Layra Reza, Scott A. Severson, Daren Dillon, Marc Reinig, Donald T. Gavel, Steven Cornelissen, Bruce A. Macintosh, Claire E. Max, “MEMS practice, from the lab to the telescope,” arXiv:1202.1566v1 [astro-ph.IM].

Thomas Bifano, Yang Lu, Christopher Stockbridge, Aaron Berliner, John Moore, Richard Paxman, Santosh Tripathi and Kimani Toussaint, “MEMS spatial light modulators for controlled optical transmission through nearly opaque materials,” Proc. SPIE 8253, 82530L (2012); http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/12.911384.

Ravi S. Jonnal, Omer P. Kocaoglu, Qiang Wang, Sangyeol Lee, and Donald T. Miller, “Phase-sensitive imaging of the outer retina using optical coherence tomography and adaptive optics,” Biomedical Optics Express, Vol. 3, Issue 1, pp. 104-124 (2012) http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/BOE.3.000104.

Yiin Kuen Fuh, Kuo Chan Hsu, and Jia Ren Fan, “Rapid in-process measurement of surface roughness using adaptive optics,” Optics Letters, Vol. 37, Issue 5, pp. 848-850 (2012) http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.37.000848.

C. Baranec, R. Riddle, A. N. Ramaprakash, N. Law, S. Tendulkar, S. Kulkarni, R. Dekany, K. Bui, J. Davis, M. Burse, H. Das, S. Hildebrandt, S. Punnadi, R. Smith, “Robo-AO: autonomous and replicable laser-adaptive-optics and science system,” Proc. SPIE 8447, Adaptive Optics Systems III, 844704 (September 13, 2012).

Renate Kupke ; Donald Gavel ; Constance Roskosi ; Gerald Cabak ; David Cowley ; Daren Dillon ; Elinor L. Gates ; Rosalie McGurk ; Andrew Norton ; Michael Peck ; Christopher Ratliff ; Marco Reinig, “ShaneAO: an enhanced adaptive optics and IR imaging system for the Lick Observatory 3-meter telescope,” SPIE doi:10.1117/12.926470.

N. Jeremy Kasdin and Tyler D. Groff, “Shaped pupils with two micromechanical deformable mirrors for exoplanet imaging,” 2 February 2012, SPIE Newsroom. DOI: 10.1117/2.1201201.004084.

Y. Lua, E. Ramsayb, C.R. Stockbridgea, A. Yurtc, F.H. Köklüd, T.G. Bifanoa, e, M.S. Ünlüd, B.B. Goldberg, “Spherical aberration correction in aplanatic solid immersion lens imaging using a MEMS deformable mirror,” Microelectronics Reliability Volume 52, Issues 9.10, September-October 2012.

Weiyao Zou and Stephen A. Burns, “Testing of Lagrange multiplier damped least-squares control algorithm for woofer-tweeter adaptive optics,” Applied Optics, Vol. 51, Issue 9, pp. 1198-1208 (2012) http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/AO.51.001198.

Toco Y. P. Chui, Dean A. VanNasdale, and Stephen A. Burns, “The use of forward scatter to improve retinal vascular imaging with an adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscope,” Biomedical Optics Express, Vol. 3, Issue 10, pp. 2537-2549 (2012).

2011

K. Enya, L. Abe, S. Takeuchi, T. Kotani, T. Yamamuro, “A high dynamic-range instrument for SPICA for coronagraphic observation of exoplanets and monitoring of transiting exoplanets,” arXiv:1110.2621v1 [astro-ph.IM].